What Remains: The Life and Work of Sally Mann was coincident with her exhibition/meditation on death. Her choice of terms for corpses, “carapaces,” jibes with my experience: when I touched the body of my father, my first thought was “this isn’t my father.” The shell felt somehow plastic, although important to others. For me, it meant nothing. Mann says for her “what remains is time and love.” But if love remains, how is love manifest? Lately, I believe the essence of love can be found in our daily meals— the moments when we stop and sustain our bodies.

What Remains: The Life and Work of Sally Mann was coincident with her exhibition/meditation on death. Her choice of terms for corpses, “carapaces,” jibes with my experience: when I touched the body of my father, my first thought was “this isn’t my father.” The shell felt somehow plastic, although important to others. For me, it meant nothing. Mann says for her “what remains is time and love.” But if love remains, how is love manifest? Lately, I believe the essence of love can be found in our daily meals— the moments when we stop and sustain our bodies.

As the holiday season approaches, it seems important to note that most key social celebrations are built around feast (or fast) days. It’s where we find the intersection of past and present in its most poignant form. A photograph, as an aide–mémoire, is quite thin. In a recent talk, Sally Mann suggested that Proust never could have written A Remembrance of Things Past triggered by a photograph. To remember, it takes the engagement of more senses. For Proust, it was a madeline. A photograph can evoke, but its affect is a surface one. Again, her use of “thin” seems apt. To stir our entire being, it takes something more than a breeze brushing across the skin, or the decayed bones of a dead pet. To really feel alive and connected to our fellows, both past and present, a meal is almost always called for.

Cooking is a craft, at times celebrated and at other times dismissed as secondary to more ambitious pursuits, “mere cookery” as Plato would have it. A meal is an opportunity, and for most, an opportunity lost, for reflecting and connecting with what it really means to be mortal. I started a recording my meals a few years ago, inspired partly by Jaques Pepin.

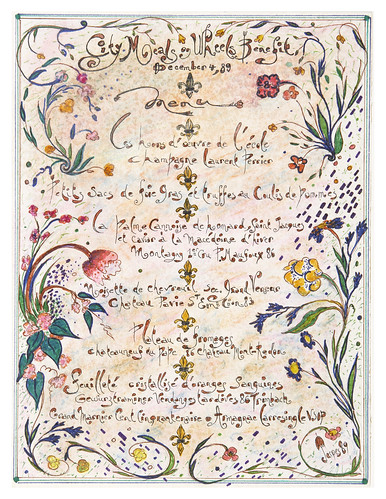

I lack the talent to draw or even hand letter menus; my experiment consists of a pedestrian list in a google document. But it started to matter to me. I liked being able to see what I used to eat. It didn’t start out as an artistic, or even poetic practice, however. It was more accurately a byproduct of reading The Good Life by Helen and Scott Nearing. They recommended keeping basic records of consumption in order to better manage one’s household, and meals are indeed a part of that. It seemed hardly surprising that Sally and Larry Mann also were moved by the Nearings, at least according to her recent Q&A. The “love” part, so apparent in Pepin’s menus, exists, albeit thinly, even in something as simple as a list of the food consumed over a period of time.

Going through my mother’s things after her death, I was always struck by the incredible number of small bits of paper with “lists” on them, listing when flowers bloomed, when relatives visited, etc. She wrote it all down increasingly as she got older. I am reminded that the origin of civilization comes down to us through time as pedestrian lists of cellar and larder inventories. If what remains is “time and love” then these records, strange as they may seem, carry with them a kernel, a seed of the human condition.

As the contentious election heated up this year, my compulsion to keep some sort of record of what was “good” about life became stronger. My wife has long kept photo sets of things that made her happy, but I’ve been disillusioned by photography these last few years. Although I dedicated most of my life to it, it just didn’t seem to be a repository of joy for me. I’ve found a way to recover just a bit of that though by photographing my meals. To combat the constant stream of political memes coming my way, I started posting those photographs to Facebook. I was surprised at the response. It seems that lots of people like food, especially in troubling times.

These photographs, for me, are simply an extension of the lists. I don’t look upon it as an aesthetic exercise at all, though I do try to capture what’s significant about the colors and textures of the food. When Lloyd Bitzer died a few days ago, I began to examine why I like taking these pictures from a different angle. Bitzer was a rhetorical scholar whose signature essay, “The Rhetorical Situation” occupied a significant part of my time in graduate school. Thinking my way through those concepts, hashed out so long ago, has brought into focus why I think of meals (not photographs of meals) as an important thing to remember, and to think deeply about.

In a grossly simplified version, Bitzer might argue that meals are a reaction to the exigence of hunger; his critic Richard Vatz might respond that we also eat as a response to being persuaded that we are hungry, while Barbara Biesecker would suggest that both of these responses deny and obscure the potential for radical transformation that occurs at every mealtime. Skipping past the Derridian doublespeak, Biesecker’s point is well placed: we don’t simply eat to satisfy a need, or eat because we’re convinced to, we eat because every time we eat we are changed by it. In turn, by exercising control over what we eat we can indeed change ourselves, with time and love.

Each meal has the potential to be a uniquely kairotic moment (last supper?). Every meal presents the opportunity to change the world, and ourselves, simply by appreciating were we are at that particular moment. Such moments, when one recognizes the potential for love and sharing, can be radically transformative. The world can be made better by understanding the complexity of our place within it.