Other than Ikea, I really wasn’t familiar with the unique qualities of Swedish design when I steered a course that way researching domestic design. The biggest discovery of the last few years, (read: “news to me”) is that other countries not only sponsored design, but actively promoted it to improve their countries and national identities.

Not so for the U.S., sadly, where apparently our contribution is cheapening everything by cost-cutting commercial capitalism. While this happened everywhere, it was worse in the US because our government did absolutely nothing to stop it, excepting perhaps the WPA in the 1930s. But the WPA was more of a jobs program, rather than a program of “moral improvement” as the efforts elsewhere promoted themselves.

In England, they had many efforts to improve design in the twentieth century, which I encountered in my readings of David Pye and Herbert Read. In Japan, the mingei movement has elements of this, though its focus was on traditional craft rather than industrial design.

In Sweden, the effort is all the more purist and moralistic due to the socialist government structure adopted there since the 1930s. And the most interesting feature of Sweden is that it embraced both tradition and machine/industrial design. To continue from a source I located last week, Swedish Arts and Crafts: Swedish Modern —A Movement Towards Sanity In Design, I feel compelled to take a few more notes.

Clearly, they were aware of the same degradation that England was concerned with in terms of industrial products and design:

The Swedish home did not escape the debasement in taste which everywhere accompanied the advent of industrialism. The arts vegetated and handicrafts slumped with the disbanding of the guilds. The urban population rapidly grew with the great influx from the rural areas. In the dismal, crowded homes of the early industrial workers there was no opportunity for carrying on the old home craft traditions, which for centuries kept alive the feeling for form and material on the farm. Instead of being producers in a self-sufficient economy, the newly created industrial labor rapidly became the largest consumer class for ready-made factory goods. The new consumer industries were able to produce cheaply, it is true, but the output was of a low standard, due to the lack of manufacturing traditions, the debasement of material, its poor finish and form. But it was not only the recently established working class that fell victim to the first raw phase of industrialism, the taste of all groups of society quickly degenerated. (8)

Note that the crisis is not necessarily the products, but the fact that people will buy them. It’s a matter of taste. The English felt the same way, and in fact the book follows directly from this to cite William Morris. The movement to resurrect traditional craft is seen as an important element in rescuing the public taste from degradation, through the home-craft institutions. It’s a social movement, front and center—but not just of a prelapsarian nationalism, but of the desire to build a new machine society. Now, over a hundred years later, it might be considered to be a worthy “manufacturing tradition.”

Some of the reading I’ve been doing suggest that Swedish design can be productively explored along two axes: Carl Malmsten on one end, and Bruno Mathsson at the other. Carl Malmsten represents the “traditional” axis.

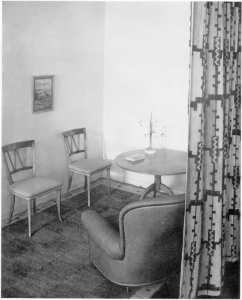

This interior is devastatingly familiar to me. It’s a lot like the way that my eldest brother’s first wife, Dana decorated their apartment in LA. Dana was Danish, oddly enough. Now, looking at it, all I can see is Shaker style—the clean lines, the austerity. The table really wouldn’t be out of place at Hancock Shaker village. But another interior from Malmsten, also from the New York World’s Fair in 1939, is a bit different:

This looks a lot more like modern Ikea, in terms of the wall units, but the settle in front is almost prairie style or arts and crafts. On the edge, indistinct and nearly out of the frame in the front right corner, is a more unusual cupboard type cabinet that is inlaid, which is displayed in a detail from the same catalog, Swedish Arts and Crafts:

It’s difficult to tell from the poor halftone, but, these are pastoral scenes with an almost Rocco flair. I suspect this is an homage to Gustavian design.

It’s difficult to tell from the poor halftone, but, these are pastoral scenes with an almost Rocco flair. I suspect this is an homage to Gustavian design.

Malmsten, obviously influenced James Krenov’s aesthetics much more than his more famous counterpart, Bruno Mathsson.

Mathsson, though he was a carpenter’s son, embraced more industrial designs.

I was struck by his chairs with built in swing aside easels, as I’ve been trying to figure out how to manage my lap top in the evenings. There are modern variants of this, of course.

Mathsson was most famous for his chairs, and there’s much to be said on that front at a later time.

For now, what I’m really most interested in are the examples of Swedish kitchens displayed in 1939.

In this design from G.A. Berg, the kitchen has been folded into the living room. Yes, that’s a sink back there divided from the sofa by cabinetry. Perhaps the most unusual feature though, is the dining table that slides between the two halves of the room. Yes, you can slide it into the kitchen for more prep area, and then back into the “living” area for serving. The dining table is on wheels. The mechanics of it are a bit clearer by enlarging the image above, though the general plan is apparent in another view, taken from the kitchen side:

What is clear is that they wanted to innovate, not simply in appearance, but in manners of work:

What is clear is that they wanted to innovate, not simply in appearance, but in manners of work:

Abroad, the Swedish efforts to create applied art attuned to modern man and his needs have been termed a style, Swedish Modern. However, by style is most often implied a distinct mode of presentation, something stationary and final. The present Swedish development in the field of industrial arts, on the other hand, is chiefly distinguished by its dynamic character. It is not a style, but rather a movement which we would like to define with the following statements:

Swedish Modern means high quality merchandise for every-day use, available for all by the utilization of modern technical resources.

Swedish Modern means natural form and honest treatment of material.

Swedish Modern means esthetically sound goods, resulting from close cooperation of artist and manufacturer. (13)