The Heimwehr [home guard] was an Austrian nationalist paramilitary group founded in the later part of the 1920s as an answer to the rise of socialism. There organizing uniform included a distinctively Austrian hat, the loden. I didn’t know what a loden looked like until I started researching hats in an effort to understand an essay by Adolf Loos.

The Heimwehr [home guard] was an Austrian nationalist paramilitary group founded in the later part of the 1920s as an answer to the rise of socialism. There organizing uniform included a distinctively Austrian hat, the loden. I didn’t know what a loden looked like until I started researching hats in an effort to understand an essay by Adolf Loos.

How is fashion determined? Who determines fashion? These are clearly very difficult questions.

The Vienna Hatter’s Association reserved the right to solve these problems in a playful matter, at least in the area of headgear. It meets twice a year around an official green table and dictates to the whole world exactly what model of hat will be worn in the following season. To the whole world, mind you. It will not be a hat that belongs to the Viennese local costume; it will not be a hat that our firemen, cabbies, idlers, dandies and other Viennese local types will make use of. Oh no, the members of the Hatter’s Association does not worry their heads about these people. For hat fashion is intended strictly for the gentleman, and everyone knows that the clothing of the gentlemen has nothing to do with the sundry apparel of the masses—except, of course, in the area of athletics, which is, as we know, an earthier activity. And as gentlemen all over the world dress alike, the Vienna Hatter’s Association sets the style for the entire Western cultural world.

(“Men’s Hats,” Neue Freie Presse, July 24, 1898)

Some things change, some things don’t. Hats often become an organizing element of cultural groups. There’s also frequently an element of nationalism. Of course the Viennese Hatter’s Association would meet around a green table, echoing the green felt loden hat. And Trump would pick the baseball cap— a surrogate for the national pastime. These days, it’s sports fans that dress alike, not gentlemen.

Some things change, some things don’t. Hats often become an organizing element of cultural groups. There’s also frequently an element of nationalism. Of course the Viennese Hatter’s Association would meet around a green table, echoing the green felt loden hat. And Trump would pick the baseball cap— a surrogate for the national pastime. These days, it’s sports fans that dress alike, not gentlemen.

The Hatter’s Association has only to publicize the form of hat which is accepted as modern all over the world, and especially in the very best circles, rather than passing off as modern a hat created by the whims of one of its members. As a consequence, exports would increase and imports would decrease. Finally, it would also be no misfortune if everyone, down to the man in the smallest provincial town, would wear just as elegant a hat as the Viennese aristocrat. (ibid, 52)

Curiously, if most people these days adopted wearing the signature baseball cap, the result would be a “leveling down” rather than an upgrade in social station. Of course, this is idle conjecture—as it was in 1898.

The times of dress code regulations are really over. But many of decisions of this Association gave a direct impact on our hat industry. The top hat will now be worn somewhat lower than last season. The Association, however, has decided that next season’s top hat should be heightened once again. And the result of this? The English hatters are already preparing now for an extraordinary volume of exports of silk hats to the Austrian market since modern top hats will not be able to be had from the Viennese hatmakers next winter. (ibid, 52)

In my hat research, I was more than a little shocked to find that Loos was right—indeed, English hatmakers had conquered the world in the late 19th century. The most popular hat in the American West was not the stetson, but rather the ubiquitous bowler.

If only the Viennese Hatmaker’s Association would have followed Adolf Loos’s advice:

The activity of the Association could also be aimed in another direction to good effect. The national hat of Austria, the loden hat, is beginning to make its tour of the world. It has already appeared in England. The Prince of Wales encountered it on a hunting trip in Austria, became enamored of it, and took the style home with him. Thus the loden hat, for men as well as women, has conquered English society. It is truly a critical moment, especially for the loden hat industry. The question is, of course, who is going to make loden hats for English society? The Austrians of course—as long as the Austrians produce those styles that English society desires. But an infinite amount of sensitivity is necessary for this, an exact knowledge of a society, a feeling for elegance and a good nose for what is to come. One cannot impose styles on these people by the brutal majority decision taken around the green table. (ibid, 52)

Unfortunately, the loden hat never did quite conquer the world. Growing up, I didn’t really attach any sort of revolutionary or outlaw significance to the bowler. If anything, John Steed was a role model for elegant conservatism, but with the same sort of sensitivity regarding society that Loos was on about.

Unfortunately, the loden hat never did quite conquer the world. Growing up, I didn’t really attach any sort of revolutionary or outlaw significance to the bowler. If anything, John Steed was a role model for elegant conservatism, but with the same sort of sensitivity regarding society that Loos was on about.

In the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, a dapper young Hungarian revolutionary named József Tibor Fejes who captured an AK-47 posed with his rifle and bowler hat. It’s the rifle that catches most people’s attention rather than the hat.

The use of hats as nationalistic symbols is deeply troubling. In fact, the entire concept of a “national” style is fraught with peril. Adolf Loos nails it precisely, with his concern about nationalism and wall building:

It would, however, be desirable for our Hatter’s association to try to develop contact with other peoples of culture. The creation of a national Austrian style is an illusion; to cling obstinately to it would cause our industry incalculable damage. China is beginning to tear down its wall, and is well advised to do so. We must not tolerate the effort of people to erect a great Chinese wall around us out of a false and parochial sense of patriotism. (ibid, 53)

One thing is certain though, the bowler is a bit of a universal symbol for those who have made it. C.C. Baxter, in The Apartment, dons his bowler when he gets a promotion, because now he feels worthy of wearing it.

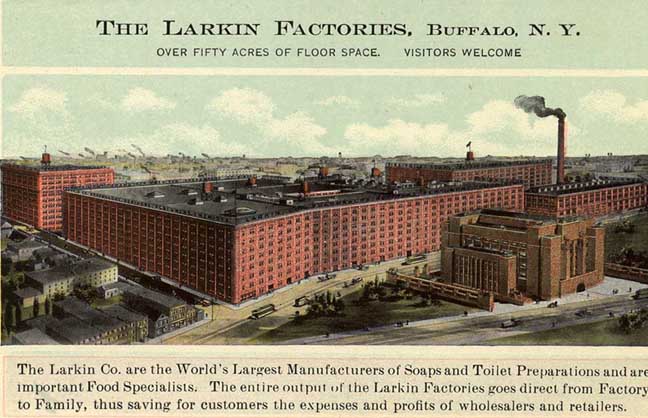

The scale of workplaces, even in the mid twentieth century, was massive. Watching Ken Burns’s documentary from 1998 on Frank Lloyd Wright, not long after watching The Apartment, I was struck by similarity in the office spaces betwen Wilder’s imagined space, and Wright’s Larkin office building:

The scale of workplaces, even in the mid twentieth century, was massive. Watching Ken Burns’s documentary from 1998 on Frank Lloyd Wright, not long after watching The Apartment, I was struck by similarity in the office spaces betwen Wilder’s imagined space, and Wright’s Larkin office building: The primary difference between Wright’s office and a New York high rise is the lack of a low ceiling, which transforms this office into a different sort of moral space—a church. In an interesting Orwellian twist, Wright’s office also features slogans to motivate the workers:

The primary difference between Wright’s office and a New York high rise is the lack of a low ceiling, which transforms this office into a different sort of moral space—a church. In an interesting Orwellian twist, Wright’s office also features slogans to motivate the workers: