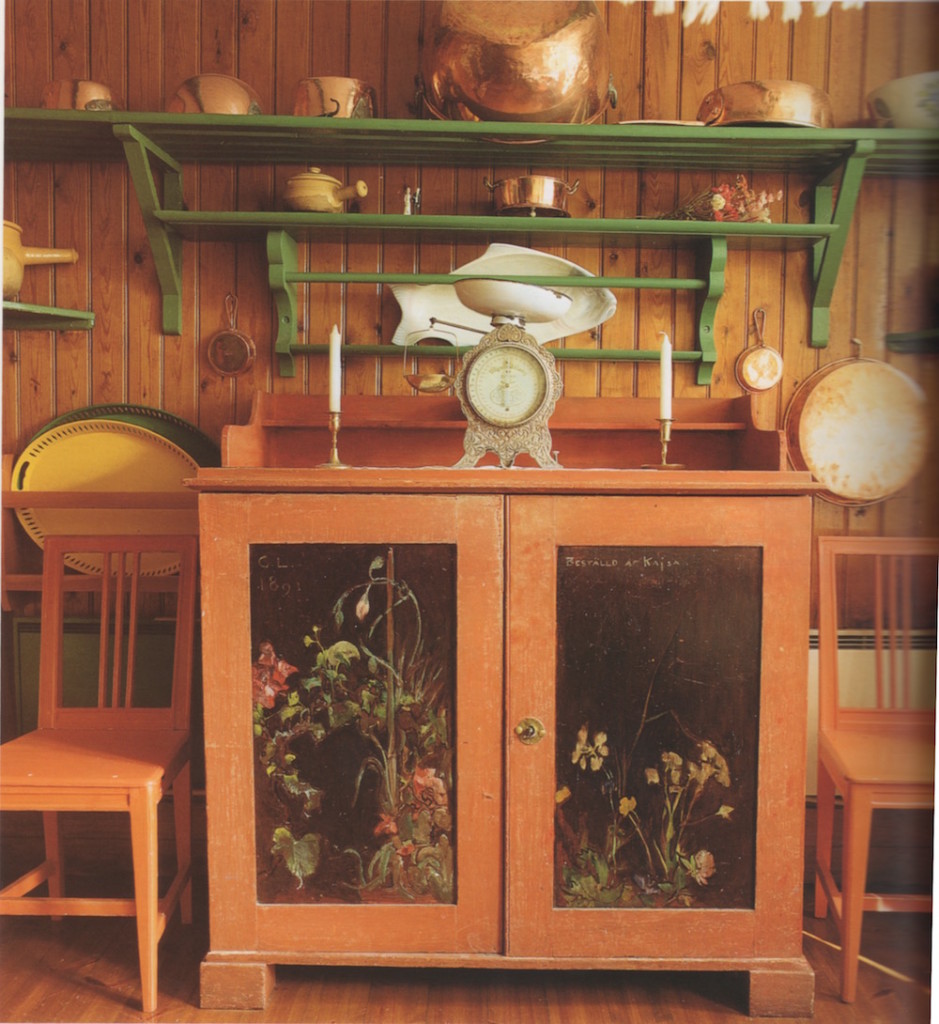

Carl Larsson could make a work of art out of even the simplest piece of furniture. The very plain cupboard, which was painted in China red, and the door panels were black-lacquered and decorated with growing flowers, in a clearly Japanese-inspired, asymmetrical composition. This piece of furniture expresses much of the young Carl Larsson’s freedom and inspiration.

Carl and Karin Larsson filled their house with old furniture, bought or given at different times. Nearly every room has a piece of furniture radiating a Baroque exuberance and a feeling for constructional clarity characteristic of peasant master craftsmen. Many of the heavier pieces of furniture probably belonged to mine shareholders, well-off land-owning farmers with a share in the local mine and arable land. Several corner cupboards and mouldings on the doors came from farmer’s homes in Dalarna. Such furniture was inexpensive at that time, and Larsson sometimes bought furniture in such bad condition that it had to be restored by his handyman. On the other hand, most of the old furniture bought for his home was well-made, of solid materials and good craftsmanship, stable and intended for practical purposes. These items are a reflection of Larsson’s nationalism, an expression of his pride in Sweden’s period as a great power in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. (Elizabeth Stavenow-Hidemark, “The Larsson Approach to Old Furniture,” Carl and Karin Larsson: Creators of the Swedish Style 187)

It’s very weird to me how the books I read tend to overlap. Chris Schwarz’s The Anarchist’s Design Book is filled with a celebration of the sort of workaday vernacular furniture gestured at (with some more ornate examples as well) in the book on Larsson I’m trying to save some snips from. I’ve never liked the word “upcycling” (apparently this term was coined circa 1994) but the practice has been commonplace for a very long time.

In fact, it’s a centerpiece of Mackay Hugh Baillie Scot’s strategy as well. In House and Garden (1906) He repeats exactly the same strategy:

The best way to secure a satisfactory result in furnishing is to have the furniture made specially for its position—a few things soundly and simply constructed which shall seem a part of the whole scheme. In many parts of the country old furniture of a simple type—gate tables, rush-bottomed chairs, bureaus, &c.—may be obtained at a very reasonable cost; and such things, with a few special made furnishings which cannot be obtained in this way, will always be at home in a house such as I have described. This old furniture has a sort of human character about it; and the varied planes of its surfaces, with its strong construction and evidences of careful leisurely work, make it inviting and homely. The modern ” Art” furniture bears testimony, on the contrary, that it is the work of a drilled automaton. Its pretence to finish is a mere superficial deceptive smartness. No human being ever loved or lingered over its completion, and its Art is the bait held out to the purchaser as a substitute for real excellence of design or manufacture. (40)

Schwarz’s “movement” towards home made furniture is not really all that new, and neither is his ranting against Ikea. It seems to me to be Arts and Crafts, through and through. What I wasn’t really expecting was to find that a bit further on, Baillie Scot comes out in full support of what Schwarz labels as “boarded furniture.” For those who haven’t been following the woodworking magazines, translates to furniture built with nails:

In the making of furniture there are two principal methods of construction in the joining of its woodwork. The simplest is that now used in making packing-cases, the wood being joined by means of nails. The more complicated is that in which the wood is joined by letting one piece into another by the use of what are called mortices and tenons.

It is a foregone conclusion nowadays that the simplest way of doing a thing is necessarily the worst way, and the nail in modern woodwork has been considered a thing to be hidden. While in all other details of construction a virtue has been made of frankness, and while the pegs of the tenon are displayed to view, the nail is sedulously concealed by all kinds of artifices. In the making of the simple kinds of furniture in which the wood is joined by nails of the kind known as clout-headed, made by a blacksmith, these might be shown without shame, and form a feature in the design, and nothing could be reasonably urged against this simple and direct “packing-case” construction for a chest or cabinet. (41)

So there you have it. Not only does he suggest boarded furniture, he also suggests traditional blacksmith-made nails over machine made wire nails. The old cliché about the more things change comes immediately to mind. But, it’s just as certain to say that craftsmanship never goes out of fashion.

Postscript: In the final essay in Carl and Karin Larsson: Creators of the Swedish Style, “The Larsson Design Legacy: A Personal View” by Lena Larsson, she tells this anecdote:

When I went into the business in 1940s [interior design], I was often asked where one could buy ‘Carl Larsson furniture.’ ; the answer was that you had to make it yourself. In 1944 Carl Malmsten published a whole set of drawings for general use. (225).

The designer/craftsman Carl Malmsten, who first encountered Carl Larsson’s books in 1907, was apparently very taken by the interior scenes created by the Larssons. James Krenov, a saint to many contemporary builders, was a pupil of Malmsten. The connections are really fascinating to me.