Never do we achieve a satisfactory performance. Things are simply not ‘fit for their purpose’. At one time a flake of flint was fit for the purpose of surgery, and stainless steel is not fit for the purpose yet. Every thing we design and make is an improvisation, a lash-up, something inept and provisional. We live like castaways. But even at that we can be debonair and make the best of it. If we cannot have our way in performance we will have it in appearance.

David Pye, The Nature and Aesthetics of Design (1978, 1964) p.14

I knew that I had run across this concept before, and it finally dawned on me where: Claude Lévi-Strauss. It’s curious, because his discussion of the bricoleur occurs in The Savage Mind, first published in French in 1962, and then translated into English in 1966. It’s certainly possible that Pye’s colleagues at the Royal College of Art were talking about it, but he didn’t arrive there until 1964; but it’s more likely that it’s just the case that there was “something in the air” that drove very smart people to think about the contingencies of human existence in similar ways. Different fields, different languages, and completely different ends in sight.

Lévi-Strauss conceived of bricoleur as a way of contrasting underdeveloped civilizations derivations and deployments of myths. Throughout, he used craft metaphors that I’m just now remembering. I think it really puts a finer point on Pye’s contributions and deviances from the anthropological theorizations of craft as a model/metaphor for human society. The bricoleur, or as footnoted in the English translation, handyman, is contrasted with the engineer. While much of what Pye is describing and attempting to theorize is closer to engineering than tinkering about like a handyman, it has a curious similarity to Lévi-Strauss’s bricoleur.

I’m not sure if that’s just a coincidence; the time-line is just too close to call. For Lévi-Strauss, the designer or craftsman, particularly of modern scientific products, wouldn’t have much in common with the bricoleur, only the “repairman” would. Revisiting The Savage Mind has reminded me why I though his treatment was interesting all those years ago.

Attempting a summary of some key points, it is important to note that bricoleur has the overtone of extraneous motion (not unlike Pye’s assessment of decoration as ‘useless labor’). The label is deployed by Lévi-Strauss to try to quantify differences between the “scientific” and “savage” mind; the savage mind consists of a limited and heterogeneous set of resources that are deployed to meet various needs, whereas the scientific mind has at its disposal groups of tools specifically gathered and grouped to meet human needs.

Pye might argue that the scientific tools are just as arbitrary and haphazard as the savage’s tools; indeed, that’s pretty much Paul Feyerabend’s contribution. Against Method was published in 1975 so it’s fair to say that such questioning was not unusual at that time. I’m not sure if the Pye’s “castaway” passage is present in the 1964 edition, or is added to the 1978. But, accepting for the moment that at least the bricoleur/castaway side of Lévi-Strauss’s formulation has merit, just what does the opposition illuminate?

The ‘bricoleur is adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks; but, unlike the engineer he does not subordinate each of them to the availability of raw materials and tools conceived and procured for the purpose of the project. His universe of instruments is closed and the rules of the game are always to make do with ‘whatever is at hand’, that is to say with a set of tools and materials which is always finite and is also heterogeneous because what it contains bears no relation to the current project, or indeed to any particular project, but is the contingent result of all the occasions there have been to renew or enrich the stock or to maintain it with the remains of previous constructions or destructions. (17)

This reminds me greatly of Chris Schwarz’s The Anarchist’s Tool Chest; Schwarz went so far as to analyze the tool lists across the ages to give a sort of historical weight to his tool selections within a tradition. The “finite and heterogeneous” tool set is contingent, but not arbitrary. Lévi-Strauss’s unusual turn from here is extruding it into a linguistic framework.

He gets there by calling a bricoleur’s tools and materials objects “a set of actual and possible relations; they are ‘operators’ but they can be used for any operations of the same type” [emphasis mine]. Defining tools and materials in this way, as relations, means that they can be used and reused only within limits. In short, their uses are finite, and they are intermediates in a potential transformation, in other words, signs:

Signs resemble images in being concrete entities but the resemble concepts in their powers of reference. Neither concepts nor signs relate exclusively to themselves; either may be substituted for something else. Concepts, however, have an unlimited capacity in this respect while signs have not. (18)

Lévi-Strauss proceeds from here to deploy his argument from analogy with a craft example:

A particular cube of oak could be a wedge to make up for the inadequate length of a plank of pine or it could be a pedestal— which would allow the grain and polish of the old wood to show to advantage. In one case it will serve as an extension, in the other as material. But the possibilities always remain limited by the particular history of each piece and by those of its features which are already determined by the use for which it was originally intended or the modifications it has undergone for other purposes. The elements which the ‘bricoleur’ collects and uses are ‘pre-constrained’ like the constitutive units of myth, the possible combinations of which are restricted by the fact that they are drawn from the language where they already posses a sense which sets a limit for their freedom of manoeuvre. (18-19)

I’m not interested here in the argument that Lévi-Strauss is making as much as I am the way that he’s making it. Tools and materials for a bricoleur are constrained; the tools of the engineer/scientist are not because he has access to the concepts behind the situation. A bricoleur/handyman is force to deal with things by using a system of predefined symbolic relations—as Roy Underhill would have it, regarding woodworking, it’s all wedge and edge. The set of tools we have at our fingertips as craftsman are defined by custom, tradition, materials, and physics.

In short, like David Pye, Claude Lévi-Strauss is looking to define the function of societies and practices by identifying their constraints. That’s really quite remarkable, given the contemporaneous nature of all this. I missed this the first time that I read it, but then I wasn’t a woodworker then. Instead, I was a photographer looking at the semiotic dimensions of this argument, which are equally fascinating:

Images cannot be ideas but they can play the part of signs or to be more precise, co-exist with ideas in signs and, if ideas are not yet present, they can keep their future place open for them and make its contours apparent negatively. Images are fixed, linked in a single way to the mental act which accompanies them. Signs, and images which have acquired significance, may still lack comprehension; unlike concepts, they do not yet possess simultaneous and theoretically unlimited relationships with entities of the same kind. (20)

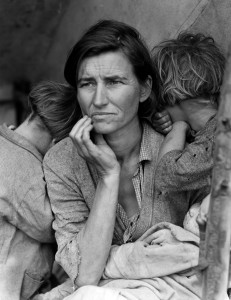

In its own way, this excursus on images is also about constraints; One might argue that an image, say Dorothea Lange’s image of Florence Thompson, must sever its fixed link to the person it references to become an open concept: “The Migrant Mother” which is then able to be set in unlimited relationship with other madonna class images. Only by defining itself as not Florence Thompson can the image acquire symbolic currency.