Instrument has a variety of usages reaching back to the middle ages. I’ve been encountering it in Hannah Arendt and Frederick Engels as the compound “instruments of violence” and in Karl Marx as “instruments of production.” Other uses include “musical instruments” and “legal instruments” –the term has been around seemingly forever. Another somewhat unique usage was by Chaucer in the Wife of Bath’s tale where he called the penis a “holy instrument” of generation. With a nod to John S. Hall, it seems to me that the overriding characteristic of most usages of instrument is that it is detachable from the human who employs it.

Musical instruments are of course one of the oldest types. The connotations are vast; these instruments are used to generate sounds, sounds that are within the grasp of human beings but always just outside of our control. There’s always the possibility of arbitrary accidents, slippages, wanted and unwanted resonances that simply can’t be completely predicted or controlled. When they work, whether in skilled or amateur hands, they produce sounds that can easily be identified as fundamentally productive, and yet through dissonance (intentional or unintentional) they provide a force that can disrupt and overthrow the status quo. The link between music and aggression is summoned at critical cultural moments, and besides its power to sooth and cajole, music also incites violence.

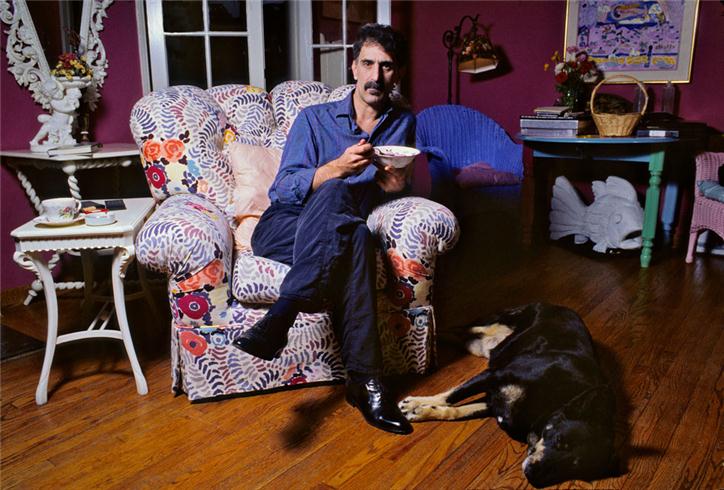

Frank Zappa once suggested, tongue-in-cheek, that in countries where beer consumption was high, nations were often warlike because they were susceptible to marching music.

I have a theory about beer: Consumption of it leads to pseudo-military behavior. Think about it — winos don’t march. Whiskey guys don’t march, either (sometimes they write poetry, which is often more horrible, though). . . .

Maybe there’s a chemical in beer that stimulates the [male] brain to do violence while moving in the same direction as other guys who smell like them [marching] — “We, as a group of MEN, will drink this refreshing liquid, after which we will get together and beat the snot out of that guy over there.”

Wine drinking countries are more associated with love songs. It’s not really a stretch to say that popular music is almost always tied to, as Chaucer might put it, “the holy instruments of generation.”

The detachable nature of instruments is perhaps best illustrated by the usage of legal instruments, which are just as old as musical ones. A writ, or a warrant carries with it the force of authority granted by law, codes which have been separated from individual human judgement. It amounts to an order, and can be directed by nobody, as evident in a building code. Laws, of course, can be arbitrary and have unintended as well as intended consequences. They can promote productivity, of course, but they can also incite violence. It’s worth noting that the production of the instruments of violence (guns, bombs, etc) is referred to manufacturing ordinance. Ordinance, of course, shares its root with ordain, that is, to issue a ruling.

The point I’m getting at is that all instruments have the potential for generative or destructive usage, and all instruments have an arbitrary and uncontrollable quality which always seem just outside of human control. That may be because they are by definition detachable from humans, and as John S. Hall, referenced earlier, suggests– they can be lost.

But there is one usage of the term “instrument” which doesn’t fit the detachable thesis. Also in use since the Middle Ages: a person may be described as an instrument of destruction; initially, this appears when writing about a murder or killing, but in contemporary usage this usage is probably best labeled as metaphorical rather than actual. People, knowingly or unknowingly, enter into causal chains (generally involving other, detachable instruments) that bring about destruction.

In What Are People For Wendell Berry writes forcefully in an essay called “Damage” of his attempt to put a pond on his property. He sought advice, and hired a bulldozer to dig one in a plateau nestled in a hillside. Everything went well at first, but then after an extremely wet fall and winter a slice of the forest above his pond broke free and slid into it. He had destabilized the hillside, despite the best advice and intentions, and was now forced to live with the scar on the land he had created. He invokes the proverbs of hell from William Blake:

“You can never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” I used to think of Blake’s sentence as a justification of youthful excess. By now I know that it describes the peculiar condemnation of our species. When the road of excess has reached the palace of wisdom it is a healed wound, a long scar.

Culture preserves the map and the records of past journeys so that no generation can permanently destroy the route.

The more local and settled the culture, the better it stays put, the less the damage. It is the foreigner whose road of excess leads to a desert.

Blake gives the just proportion in another proverb: “No man soars too high if he soars with his own wings.” Only when our acts are empowered with more than bodily strength do we need to think of limits.

No thought or word called culture into being, but a tool or a weapon. After the stone axe we needed song and story to remember innocence, to record effect– and so to describe the limits of what can be done without damage.

The use only of our bodies for work or for love or pleasure or even for combat, sets us free again in the wilderness, and we exult.

But a man with a machine and inadequate culture— such as I was when I made my pond— is a pestilence. He shakes more than he can hold.

Berry is in line with Engels in thinking that in order to do violence, man requires detachable instruments. There’s another discussion of pond construction that bears mentioning here, which involves instruments of a different category.

In a chapter of Cræft: an Inquiry into the Origins and Meanings of Traditional Crafts Alexander Langlands describes pond construction, both his own attempts and the archeological evidence regarding a particular pond the Oxna Mere. It is situated within a series neolithic clay ponds in Wessex, along well worn migratory routes. the consensus is that these ponds were human made, using livestock. It’s short sighted to think that all extensions of human strength are recent developments in the construction of mechanisms, or that instruments began in the industrial age.

Langlands attempted to work backward from the ethnography of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century pond practices to determine how these ponds were built and maintained. Clay is a porous material, and in order to make them hold water it was longstanding practice to drive herds of animals across the area to compact the clay to make it hold water. Obviously, there’s a lot of technique/craft involved. Why does this matter? As Langlands argues:

The implications of using puddled chalk were important to me in the context of the Oxna Mere. Ultimately, its significance lay in the simple revelation that if you had the knowledge and the skill to puddle chalk, you could create a watering hole using materials sourced entirely from the hilltop. In turn, this facility would make an important contribution to the methods of husbandry used by valley community in that it enabled them to exploit valuable resources of summer grazing in a more effective manner. This is the kind of thing I get excited about: resourcefulness on a level almost inconceivable to the post-industrial pond maker whose favored materials were concrete and asphalt. (250)

What seems to be at work here is the use of animals as instruments in a way inconceivable to us now; we think of them solely as raw material. They fit the parameters I was looking at earlier. They are arbitrary and frequently outside human control, capable of both generative and destructive aspects. And yet they have been successfully operating in concert with human beings assuring our mutual survival; without herd animals we wouldn’t survive, and with our coordination in the construction of ponds in the neolithic period, they also thrived and multiplied.

If we admit the possibility of a living instrument, there’s another aspect consider. Marx offers another paradigm for instruments. His class theory (and theory of alienation) presumes that man himself can be transformed into an instrument.