Studying domestic architecture has lead me some strange places. Adolf Loos’s essays reminded me that I didn’t know squat about Austria, and the process of figuring that out I keep ending up back in England. The architectural zone that Loos was writing about is marked by the historicism promoted by Jacob von Falke. The location— Ringstraße, the ring road— gave birth to Ringstraßenstil or ring road style.

The Ringstraße follows the path of an old fortification, a wall erected in the 13th century to protect Vienna financed by the ransoming of Richard the Lionhearted, who coincidentally was a lover of walls himself. He claimed that he could protect his own Château Gaillard (the saucy castle), perched over the Seine, if its walls were made of butter.

Historically, on many levels, houses have been centers of power. Wielding a lot of power, the Norman kings like Richard, did a lot of business in the keep, most often a square structure behind walls like Château Gaillard. Apparently, due to architectural constraints (primarily the difficulty in constructing strong roofs) these places were often quite small.

Austrian towns like Vienna liked surrounding themselves with walls. Many are still apparent other cities nearby, like this nice double wall in neighboring Bratislava, Slovakia:

Austrian walled towns began appearing in the 11th century, and the one in Vienna was a feature of the town until the 19th century, when it was torn down the surrounding buildings were kept on the newly constructed Ringstraße, a historical district. It was a showpiece for the city; Sigmund Freud used to go for strolls there.

Architecture, as Loos reminded me, is often rhetorical. The renovations of many of the European capitals in the mid 19th century was fortification of a different sort. Baron Haussmann’s renovations of Paris for Napoleon III were part modernization, and part crowd control. Long straight streets make it easier to move troops, and harder for revolutionaries to erect barricades: the Ringstraße discourages revolution, a clear and present danger when you have a ruling minority, as you had in Vienna, the main capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

What was really refreshing to me, examining Swedish architecture, was the lack of emphasis on fortification. Though the farm buildings were distributed around a central latrine area, it didn’t seem to be for protection; it was a practical, rather than persuasive, arrangement.

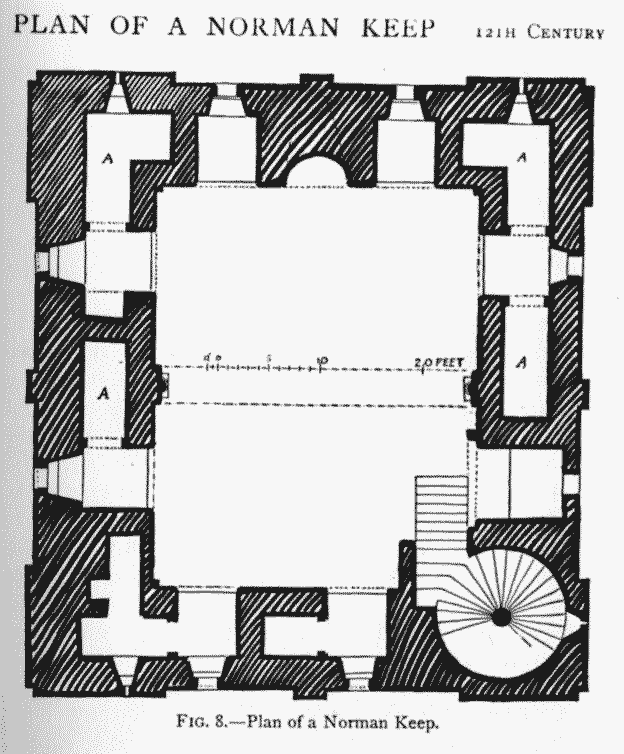

How were dwelling interiors initially divided? What was inside the big Norman keep? I found some information in The History of Everyday Things in England (1922) by Marjorie and C.W.B. Quennell that I haven’t found in more modern resources:

The plan of the keep is very much the same on all floors. The lower, or ground, floor below the entrance served as a storehouse for the large quantities of food which must have been required during a siege.

At the first floor, or entrance level, was the guard room; above this, on the second floor, was the great hall, with its galleries all around; and above that, one more floor, probably used as a dormitory. The well of the castle was in the keep so that the garrison might be sure of water in case of siege.

The staircase was in one of the angles, and lead up to a square tower opening on to the battlements, with similar towers on the other three angles of the castle. Here the guard did sentry-go 75 feet above the level of the top of the mount, so that they could see a long way over the trees and prevent surprise by the enemy.(15-16)

The small rooms (A) are generally conjectured to be the bedchambers of the principal members of the family. Googling around a bit more, I’ve identified this particular Norman keep as Hedingham Castle in Essex; what makes it of interest is the centrality of the Great Hall:

The illustration, nicked from the web because I couldn’t create a better scan myself, shows a non-arched roof and a large social space without furnishings. It’s generally acknowledged that medieval furniture was all portable, tables and stools and such. This is the origin of the sort of “King’s room” that Adolf Loos was discussing in his essay on “Interiors in the Rotunda,” which became increasingly crafted to impress across the ages. The small ancillary rooms, visible in the floor plan, weren’t really useful for all that much I suspect—a bed with a tiny window/porthole to the outside.

The illustration, nicked from the web because I couldn’t create a better scan myself, shows a non-arched roof and a large social space without furnishings. It’s generally acknowledged that medieval furniture was all portable, tables and stools and such. This is the origin of the sort of “King’s room” that Adolf Loos was discussing in his essay on “Interiors in the Rotunda,” which became increasingly crafted to impress across the ages. The small ancillary rooms, visible in the floor plan, weren’t really useful for all that much I suspect—a bed with a tiny window/porthole to the outside.

But this does not mean that the complexes of structures weren’t differentiated. Take for example, this breakdown (including furniture) of a medieval manor, Chingford, granted by the Chapter of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, in 1265, to their Treasurer Robert Le Moyne:

He received also a sufficient and handsome hall well ceiled with oak. On the western side is a worthy bed, on the ground, a stone chimney, a wardrobe and a certain other small chamber; at the eastern end is a pantry and a buttery. Between the hall and the chapel is a sideroom. There is a decent chapel covered with tiles, a portable altar, and a small cross. In the hall are four tables on trestles. There are likewise a good kitchen covered with tiles, with a furnace and ovens, one large, the other small, for cakes, two tables, and alongside the kitchen a small house for baking. Also a new granary covered with oak shingles, and a building in which the dairy is contained, though it is divided. Likewise a chamber suited for clergymen and a necessary chamber. Also a hen-house. These are within the inner gate.

Likewise outside of that gate are an old house for the servants, a good table, long and divided, and to the east of the principal building, beyond the smaller stable, a solar for the use of the servants. Also a building in which is contained a bed, also two barns, one for wheat and one for oats. These buildings are enclosed with a moat, a wall, and a hedge. Also beyond the middle gate is a good barn, and a stable of cows, and another for oxen, these old and ruinous. Also beyond the outer gate is a pigstye.

It isn’t incredibly clear exactly how many buildings there were. Places are broken down by function, not by building. For example, the kitchen and bakery were generally separate buildings, no doubt due to the smells and complexities of cooking on open fires, but also because large spaces simply couldn’t be effectively covered by roofing.

By the time we get to Edward I (1272 to 1307) interiors begin to change significantly. Here, we finally begin to see the sort of “private space” for a king that Adolf Loos alludes to. What is striking to me in his essay “Interiors in the Rotunda” is the distinction between public/ceremonial spaces, which are by design “rhetorical” in the sense that they must persuade the inhabitants of the social and political power of their owners. The private chamber, for Loos, is a different space entirely. While it can be poetic, it must above all be personal.

Edward I’s wife, Eleanor of Castile, brought many innovations into the dwelling spaces of Kings. I really must read Sara Cockerill’s recent book, from the sounds of this excerpt:

So why does Eleanor of Castile deserve to be rescued from the scrapheap of history? One very good reason is because she was far from unobtrusive; she was a remarkable woman for any era. Eleanor was a highly dynamic, forceful personality whose interest in the arts, politics and religion were highly influential in her day – and whose temper had even bishops quaking in their shoes. Highly intelligent and studious, she was incomparably better educated, and almost certainly brighter, than her husband. She was a scholar and an avid bookworm, running her own scriptorium (almost unique in European royal courts) and promoting the production of illustrated manuscripts, as well as works of romance and history. Equally unusually she could herself write and she considered it a sufficiently important accomplishment that her own children were made to acquire the skill.

She also introduced numerous domestic refinements to English court life: forks, for example, first make their appearance in England in her household and carpets became sought after in noble circles in imitation of her interior design style. She was a pioneer of domestic luxury: she introduced the first purpose-built tiled bathroom and England’s first ‘fairy tale’ castle – both at her own castle of Leeds, in Kent. She revolutionised garden design in England, introducing innovations – including fountains and water features – familiar to her from Castile.

The fork was an important innovation, as was the interior bathroom. Jabon de Castilla, or castile soap, was an important export from Castile in the Middle Ages, so it makes sense that Eleanor would be attached to bathing. Roofs got better and the interiors of buildings were differentiated into different spaces, as Muthesius recounts, and the specialization apparent in manor complexes transferred into the interior in ways a bit unique to England, although with obvious international components.

What strikes me in all this is the transformative power of rhetorics of display. I think that Loos is right to insist that personal spaces must be individual, and the rules are simply different for public, rhetorical spaces. They can’t be directly compared at all, though we’ve been conflating them for years. As walls come down, though the physical barriers are transformed, psychic barriers between public and private are permeable.

If you look at the public display of interiors, say on Pinterest, what you see are tidy stylish public spaces meant to create desire, to persuade—not spaces meant to be lived in. Living is messy, and usually not in need of fortifications.