It surprised me to hear that dab was a printing term associated with stereotyping. I also found it strange that it would be associated with dance move, or internet meme, or drug use.

Dab entered the English language around 1300, with no known origin, both as a verb and a noun. It started as a slap, a light blow, also used figuratively as in “poking fun” at someone. In the 18th century, it was associated with soft substances, though I suspect they weren’t talking about Brylcreem. It also meant to apply just a small amount. An obsolete sense used in typeseting meant inserting a wooden type ornament into soft metal to cast it in more durable form.

Incised printing, in some forms of engraving and photogravure, has some dynamic range in that deep channels in the plate can hold more ink and thus print darker, making them somewhat analog in that degrees of gradation are possible. Texture is given primarily through the use of patterns of stippled dots, like grains, or lines arranged in parallel a bit like grain in wood to increase the surface area which would hold ink in its recesses increasing density.

Relief printing, as in woodcut or typeset text has two states: ink or no ink. Relief printing is a digital process. A small amount of ink is dabbed or rolled on the surface of the plate; too much ink and the plate is unintelligible. Grain isn’t a factor in woodcuts, as the wood is oriented with its grain perpendicular to the impression for maximum strength and the ability to hold fine detail. Line and and stipple are also used for much the same fashion as in burin engraving on metal, but without the same sense of depth and range because of the increased saturation, rather than density, of ink.

Historically, the wood used for woodcuts comes from boxwood, the same popular topiary shrub seen everywhere today. Needless to say, there are distinct limitations to materials used in reproductive technologies. Boxwood is slow growing, and almost never reaches beyond 3-4 inches in diameter. Pieces are cut into cross grain disks of the same height as the metal type to be used, and in order to make larger illustrations, multiple pieces are carved separately and clamped together in the press. In the 19th century, this was actually useful because labor could be divided between several journeymen to make plates quickly instead of the laborious, sometimes multi-year procedures associated with burin engraving.

Carving against the grain has some disadvantages. Wood grain behaves like a cluster of straws, soaking up liquid and swelling to weaken it. Thus, stereotyping for larger production runs was a necessity, not an option. At the turn of the 18th century, though, smaller publics and lower production made the production of elegant artistic works possible, like Thomas Bewick’s A General History of the Quadropeds from 1790.

Accuracy in reporting wasn’t really an issue for most early instances of visual communication. There was big money circulating in print, mostly for publishers, and a large pool of journeyman able to churn out words and images. Illustrated newspapers were a big success by the middle of the nineteenth century. But there were a variety of competitors in the race to pander to, as well as create, a public taste in visual representations. The invention of photography in 1839 did not revolutionize or overthrow existing print regimes. Photographs were often raw material for engravings, discarded after sketches or engravings from them had been created.

One of the major markets for publishers was reproductions of popular works of art. Henri Delaborde, writing in 1856, saw little future for photography as a useful tool for this:

In reproducing art, it is the inevitable inability to discriminate between what should be transcribed and what should be interpreted, that is the fatal disability which will eternally condemn photography to an industrial role that is beneath and outside the bounds of art. Photography can but parody the appearance of its subjects. Printmaking manages to seize its intimate appearance. Nowadays we are inclined to content ourselves with inanimate reproductions. Nothing more. Should this be sufficient for us? Have we lost our appreciation of art because of our sudden interest in a new discovery?

It seems odd that the lines, crosshatches, and stipples of early printing processes would be be preferred to smooth gradations of tone provided by silver or platinum grains clumped at the papers surface. There were limitations, to be sure— largely due to the lack of color processes— but interpretations of artworks were more prized than accurate reproductions. For a time, relief prints, intaglio prints, and photographs all competed for the same sector of the art market: reproductions of paintings. For news, there was simply no competition for woodcut printing. Photographs were used to provide an index to appearances, but the report was created by a committee of artisans. William Ivins identified this cultural phenomena, in his final remarks in 1953:

In a way, my whole argument about the role of the exactly repeatable pictorial statement and its syntaxes resolves itself into what, once stated, is the truism that at any given moment the accepted report of an event is of greater importance than the event, for what we think about and act upon is the symbolic report and not the concrete event itself. (180)

The market for images demanded, rather than depth and accuracy, a human interpretation of whatever event was being reported. This was slow to shift. Taste did not begin to shift until after one more revolution in print culture, lithography. It was lithography that put art in everyone’s home. The ascendency of photography was slow, and only really took off when it lost its subtle gradations as it was digitized into halftone dots.

The emphasis on the human touch in the 18th and 19th century, perhaps even into the 20th reflects real concerns about the nature of perception and the imperfections of technology. It seems entirely fitting that Bewick, the pioneering woodcut artist, used a carving of his thumbprint as a signature. Curiously, in the slang of 20th century noir, a fingerprint is a dab.

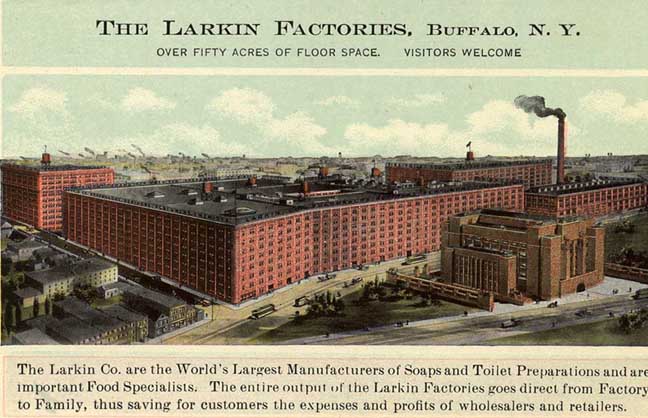

The scale of workplaces, even in the mid twentieth century, was massive. Watching Ken Burns’s documentary from 1998 on Frank Lloyd Wright, not long after watching The Apartment, I was struck by similarity in the office spaces betwen Wilder’s imagined space, and Wright’s Larkin office building:

The scale of workplaces, even in the mid twentieth century, was massive. Watching Ken Burns’s documentary from 1998 on Frank Lloyd Wright, not long after watching The Apartment, I was struck by similarity in the office spaces betwen Wilder’s imagined space, and Wright’s Larkin office building: The primary difference between Wright’s office and a New York high rise is the lack of a low ceiling, which transforms this office into a different sort of moral space—a church. In an interesting Orwellian twist, Wright’s office also features slogans to motivate the workers:

The primary difference between Wright’s office and a New York high rise is the lack of a low ceiling, which transforms this office into a different sort of moral space—a church. In an interesting Orwellian twist, Wright’s office also features slogans to motivate the workers: