Apparently, the latest software change has relocated my feed. Adjust if you like.

Category: tPA 5

Durable Goods reprise

I once wrote long ago about being interested in “composition” in the broadest sense. At the time, I was thinking in terms of words and images rather than objects. Surrounding the period when my mother died, I began to really consider the concepts surrounding “durable goods” because when confronting just what is important when faced with mortality. Like most people, I suppose, I hadn’t really thought much about the objects that fill our lives, and as my mother’s life was stripped down to the essential goods, I began to wonder about the matter of matter (as opposed to words/images, or more descriptively, eidolons).

In 2010 I came pretty close to putting some perspective on things when I tried to theorize about the relationship of craft to words, images, and woodworking (my latest sidetrack). To bring this decade long obsessive/compulsive spasm up to date, lately I’ve been building and thinking about furniture and household items (treen). I’ve thought several times that I should be compiling a bibliography of sources about this latest phase, which has moved far outside my usual comfort zone of art and literature. Thankfully, my wife has been teaching a seminar on rhetorics of craft which has brought new levels of focus to my scattered thoughts on the subject. We’ve been talking about craft a lot.

It dawned on me a few days ago that one of the reasons for the shift in subject areas (though not in methodology, strangely enough) is because I figured out a while ago that I am happiest when I am where I am. The place I live now was central to the Arts and Crafts movement in America during the early twentieth century. The original Stickley factory is just down the street from me. Consequently, it is all too natural to become obsessed with furniture history. After reading deeply on Arts and Crafts, the last month or so my attention has shifted to the Shakers (the original settlements are not far from me in the Hudson valley). In that shift, there’s been an interesting twist.

I’ve been pretty appalled the constant shilling for products by most writers on woodworking, even those who claim to be free from commercial interest. To acquire the best tools, seems to be a matter of constant worry for contemporary woodworkers. That attitude of connoisseur is pretty pervasive, particularly when boutique capitalism masquerades as anarchism. I haven’t been able to even consider building a thousand dollar workbench in expensive hardwood, or saw benches made of cherry wood, etc.. I really want to build furniture, not a collection of pretty tools. Visiting the workshops at Hancock Shaker Village revealed some unusual things– scrollsaws and lathes in every shop, for one thing. The scrollsaw has become a tool for fretwork alone, these days. But the shakers (who eschewed excessive ornament) still found solid uses for the tool, apparently. And most things in the Shaker shops seemed to be made of dull pine and poplar, not fancy hardwoods.

Shaker furniture used hardwoods when appropriate, but was not shy about using softwoods or paint when they would be suitable as well. Reading about some elements of furniture design in the UK in the early twentieth century, the phrase “fit for purpose” as a slogan appears. The language, taken from consumer protection law in the 19th century, makes sense. That’s a driving element behind twentieth century design in America as well, though it isn’t so clearly stated. I found myself wondering just why the idea of a cherry saw bench bothered me so much. After all, hardwoods are certainly “fit for purpose” for shop fixtures, they’re just expensive. Then it came to me— they are just plain ostentatious— conspicuous consumption of scarce resources for commonplace use. So “fit for purpose” isn’t the only factor in selecting material, it’s also important to me that there me some degree of humility.

Stickley furniture, with its quarter-sawn oak and heft is interesting to me but as a consumer product, it seems unsustainable. Only a select few can afford it. I like the philosophy behind some of it, and its solidness, but I’m afraid I’m slowly drifting away from it. I keep building Stickley style small pieces because they are nicely joined and economical in material for the most part, but I can’t see myself building the major pieces. My heart is headed somewhere else.

Round 6

It’s been about nine months since I last posted anything on this domain. Much has happened, and there have been a lot of miles traveled (mostly mentally). The impetus to break the silence and say something here (rather than sneaking about on my ancient domain) is twofold: first, Movable Type has finally become completely evil and announced that they are discontinuing support for the software I have used for the last dozen years. Second, I’ve actually regaining some desire to write.

Things are different now. I’m now nearly alone in the world with only a few surviving old friends and no relatives beyond a few cousins and nephews. My closest brother died last week. It seems that the last time I wrote, I was writing memories of dead people. I don’t want to do that (which is partly why I stopped writing publicly). To have that out there as my public “face” was a really skewed view of my mostly happy life. Since I have pretty much failed as a member of virtually any club that would have me, it seemed like a reasonable gesture to try to write down some current thoughts for those who will survive me. No rush I suppose though; I’ve got plenty of time (I think).

Therefore, the time has come to create this Public Address 6.0; I’m not really sure that I fit the previous boxes that I used to stuff myself in. Time for a new container.

Hive minds

We have seen how it is originally language which works on the construction of concepts, a labor taken over in later ages by science. Just as the bee simultaneously constructs cells and fills them with honey, so science works unceasingly on this great columbarium of concepts, the graveyard of perceptions. It is always building new, higher stories and shoring up, cleaning, and renovating the old cells; above all, it takes pains to fill up this monstrously towering framework and to arrange therein the entire empirical world, which is to say, the anthropomorphic world.

On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense, Frederich Nietzsche.

One of the most difficult things to cope with this past few years is the constant confrontation with death. Since my mother died, the most common question that pops into my head is “does it really matter?” I watched her lose her mind, unafraid of death for the most part and quite accepting of it. What mattered mostly were the little things, the little bits of dignity that so slowly slipped away from her. For the last five or six years of her life, I called her everyday. That is, until she could no longer stay coherent long enough to speak on the phone. I missed those calls, as they became less and less frequent before her death. I’d like to be able to say she slipped away quietly into a dream, but it was more like she just got lost in a nightmare that she never woke up from. It was chilling, filled with paranoia and delusions, and unsettling to the core.

In a profound sense, my world just collapsed. Her passing wasn’t “natural” to me the way my father’s was. My father simply drove himself to the hospital and died. My mother faced a long, slow, and unpredictable decline. I’d been thinking up to this point that my life was improving, moving ahead. I had more respect, had managed a more secure financial outlook, had a secure and satisfying romantic relationship and an intellectual project that seemed all-consuming; but what happened to my mother threw me. Is this what really happens? Are people inevitably reducible to (streamlining Earl Butz) to the desire for comfortable shoes and a warm place to go to the bathroom?

I’m finally managing to get some distance from the problem, but nothing seemed very important after that beyond simple human kindness. I put down my scholarly projects due to a deep depression and an inability to concentrate, and moved to other pursuits that were more tangible and bound to objective realities. I didn’t stop theorizing, so much as I directed my hive-building into other areas. For the first time in my life, I’m buying my own home. I disconnected my self from Universities for a time, and began a different sort of life that wasn’t centered on the catacombs of scholarship, in a hut as far away from it as I could manage.

Whereas the man of action binds his life to reason and its concepts so that he will not be swept away and lost, the scientific investigator builds his hut right next to the tower of science so that he will be able to work on it and to find shelter for himself beneath those bulwarks which presently exist. And he requires shelter, for there are frightful powers which continuously break in upon him, powers which oppose scientific truth with completely different kinds of “truths” which bear on their shields the most varied sorts of emblems.(ibid)

I hadn’t really thought about the time I spent at the University of Minnesota that much until the past week or so, when I started thinking about Vicky Mikelonis. I was excited to take her class on “Models and Metaphors.” We read deeply into metaphor theory, which I had first encountered in Paul Ricouer’s The Rule of Metaphor which I read alone at University of Arkansas. I had a lot of trouble with it, and there really wasn’t anyone there to ask about it. With Vicky’s help it made a lot more sense the second time around, as did the volumes of theory we read along with it. Vicky used Nietzsche’s “On Truth and Lies in an Extra-Moral Sense” as the capstone for that class.

I hadn’t thought about it until lately, when a colleague at SU mentioned teaching with Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language.” The Orwell now horrifies me with its privileged white male perspective on language. I taught with it my first few semesters as a teacher and came to loathe and discard it quickly. It only took a few moments to remember the Nietzsche as a potential alternative view, with its major problem being that it would be incomprehensible to undergraduates while the Orwell is easily digested. Both see language as central to being human, tied to habit and convention and sometimes leading us astray. The difference is that Nietzsche accepts the inevitability of this rather than railing against it. The more I read the Orwell, the more I got Pete Townshend’s “Won’t get fooled again” stuck in my head. How barbarous to think that your own tired concept of language isn’t just as barbarous as any that has been used before? I haven’t been able to look away from the Nietzsche essay for the last week, and the more I looked at it the more I remembered Vicky.

The drive toward the formation of metaphors is the fundamental human drive, which one cannot for a single instant dispense with in thought, for one would thereby dispense with man himself. This drive is not truly vanquished and scarcely subdued by the fact that a regular and rigid new world is constructed as its prison from its own ephemeral products, the concepts. It seeks a new realm and another channel for its activity, and it finds this in myth and in art generally. (ibid)

We read glorious theories in that class, which always have some sort of fatal flaw. Vicky passed away in 2007, and I always wondered why she never wrote much on the subject of metaphor outside of pedagogical applications. She taught technical writing, primarily, and the things she taught made a deep impact on the world and her students. She could walk through the air of complex theories, never losing sight of the real and grounded human potentialities behind them. One of her favorite comparisons about the moment at which we truly “get” a metaphor and see its aptness, as the same sort of “ah-ha” moment that we get the punch-line of a joke. She took these theories and applied them to how people learned, not in a dry way, but in a way that made you smile with the sheer humanity of it all. She seemed fascinated and interested in my comparatively arcane research agenda (19th century photography), and unlike most of the professors I knew at UMN was always available just to chat about strange and beautiful things. I knew she was sick, but I never thought about her dying. She was always too busy living to get dragged down by death. In a strange coincidence, she was also the only woman besides my mother to consistently call me “Jeffrey” even though I frequently protested.

I haven’t read the Nietzsche since she passed, and since my mother passed. It takes on a new sense of urgency for me now, although the drive to compare, and shape metaphors was stronger then. Now, I’d rather build than write. I want to reshape my world, not conceptually but physically— and not as art, but as craft.

This drive continually confuses the conceptual categories and cells by bringing forward new transferences, metaphors, and metonymies. It continually manifests an ardent desire to refashion the world which presents itself to waking man, so that it will be as colorful, irregular, lacking in results and coherence, charming, and eternally new as the world of dreams. Indeed, it is only by means of the rigid and regular web of concepts that the waking man clearly sees that he is awake; and it is precisely because of this that he sometimes thinks that he must be dreaming when this web of concepts is torn by art. (ibid)

Sometimes I feel like I’m drifting away, only brought back when I shape actual objects to fill my world with. It’s a struggle to be awake.

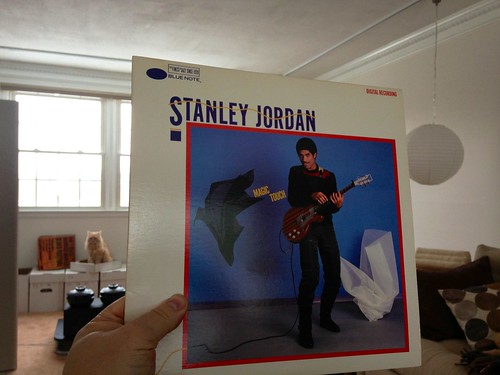

Magic Touch

Off and on for the last year or so, I’ve been trying to listen to all my LPs. It’s a major task, given that I’ve got a few thousand. But with my acquisition of a record cleaning machine it made sense. I’m doing it in alphabetical order, and I think today I’ll manage to finish “J”. I took a look through my archives, and I guess it’s been almost two years— I think I got the cleaning machine for my birthday in 2011. It seems weird, and sad, that in all the time I’ve been writing I’ve never said anything about Ken Hunter— I think of him from time to time, and it’s always with a smile. Ken was the one that got me listening to more jazz, and jazz of lighter varieties like Stanley Jordan.

I suppose one of the reasons why it becomes difficult to get up the energy or enthusiasm about writing is the fact that the majority of people that I’d really like to have as an audience are dead. Kenny was one of the first that I lost, and for the most bizarre of reasons. He moved away, a year or two before I left Bakersfield, to take a job as a prison guard on the coast of California. I heard, just after I arrived in Arkansas, that he was playing basketball one day and a blood clot tore loose in one of his legs and caused a heart attack. He died in the emergency room. He had just started a family, and the loss to them and his friends was devastating. It was one of those cases where you just can’t understand why such a young, healthy guy is just suddenly gone. I’m not sure he was even 30. I don’t think he was.

I met Ken when I was working at Leo’s Stereo. He was one of the stock people, along with Wilson Gambi, (a Nigerian fellow that I liked as well). When you stepped off the floor to take a breather, Ken was always there to talk music with, and though we didn’t always agree, we respected each other’s opinions. One of the things that defined Kenny was his faith, and he would always joke around with the sinners who worked in that industry with very little sense of judgement. Salesman, aren’t generally the most moral people, and for Ken even the most vile of us wasn’t beyond redemption. He tried to preach, in subtle ways, in every act of kindness that got us all through the day smiling. I wasn’t surprised that he moved on to being a prison guard. He wanted to make a difference in the world, and hanging out with the converted wasn’t what he considered to be the most important thing to do.

I wasn’t much interested in Christian music when I met him, and I suppose I’m still not that interested in it. But I was interested in Kenny’s music. He never really recorded anything much that I know about, though I suppose it’s possible since he was always in bands and some of those bands did go on to record. Mostly, I just went out to see him at coffeehouses and such.

I think about Ken every time I put on certain records. I cannot help but wonder how such a kind and sweet man could have just died like that, while so many of my less virtuous friends (including myself) seem to keep living. But thoughts of Kenny are always happy ones, because he simply wouldn’t have wanted it an other way.

Interuptus

Halloween

I haven’t been able to really dedicate any time to writing since I’ve started teaching again. Oh well. Perhaps the muse will visit another day.

Stuck on time

When I was a grad student in Minnesota I had a persistent difficulty with Aristotle’s framing/criteria for three genera causarum (general causes) for speech. On the surface, it seems easy. The first general cause for speech is forensic, or legal. This goes back to the earliest writings on rhetoric surrounding the story of Corax and Tisias and the usage of speech to defend property in the courts. At issue, in that case, is just who had owned particular pieces of property. It makes sense, then, that forensic rhetoric tends to look to the past: did they do it or didn’t they, to put another legal twist to it.

The other distinctions are harder for me to grasp. Later authors complicated thing by adding more nuanced treatments of general causes, and that really muddies the waters. Aristotle’s neat usage of three categories is certainly generic– adding more primarily makes the distinctions more specific. They also seem to sort well along a continuum of past/present/future. Legislative rhetoric, for example is easy: should we do it or not? Obviously, the general cause is arbitrating future behavior. But where i always got tripped up is present-directed rhetoric, usually labeled as epidactic rhetoric or more recently, rhetorics of display. At issue, at least in the classical framing of the problem, are matters of praise or blame.

Yesterday, I think I figured out my problem. You see, I always wanted to class speech directed at praise and blame as focused on the past. All evidence marshaled for praise or blame resides there, but the desired action rests in the present. However, the same could be said of forensic rhetoric– one can’t lobby for past action. The distinction shows cracks in its foundation here. As rhetorics of display, present focus is defensible as the bringing forth in the present both past and potential future actions to make people see. Remember that the focus here is on general causes, hence to decide past/future action is obviously different than simply showing something to an audience. Here, action must be framed as praise or blame, adherence or separation from a proposed view in the present. This seems confusing to me, so I always got it wrong.

This popped back into my head when i was thinking of a different sort of causation– material cause. I’ve been obsessed by that for a few years now. When I taught a photography class years ago I structured the fundamentals as time, space, and light. I tend to think of light as the best candidate for a photograph’s material cause, but photographs definitely have a proscribed relationship with time as well. Space will have to remain outside the discussion or I will never get this composed. The time of photographs, casting aside for a moment the mundane issues of shutter speeds or motion pictures, seems to me to be a perpetual past.

Makes sense– photography, the form of display that I am most familiar with, is always directed at the past. In fact, in a profound sense photographs generate what can only be described as a perpetual past. The “news” photograph is an oxymoron because whatever it displays always occurred in the past. You cannot photograph the future. The act of photographing something always arrests its subject like an insect in amber, dooming it to be a sort of curiosity. Good photographers embrace and work through that. It’s photography’s most commonplace trope. I was reminded of that today when reading a vivid description of recreating Britannia, that irrepressible panegyric figure, updated for the recent olympiad:

In any photographic situation where there is a danger that it might go all wrong, where the execution can be way too literal, I always try to steer it back towards the one element that is the most important: spirit. In this case, Laura Trott is a 20 year old girl from Hertfordshire. A week earlier no one, including me, outside of the world of track cycling had heard of her. In seven days she, among several others, had come to embody an ideal of how we would like our country to be. Hard working, modest, humorous, good at stuff and very much alive. Binding her up with spears, shields, togas and chariots would drag her down more than anything. How to make it work?

I close my eyes and I think of the canon. The canon are the photographers I draw on in times of doubt. They give me comfort, solace and inspiration. They include Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, Bruce Weber, Lee Friedlander, Sally Mann, Corrine Day, Glen Luchford, Erwin Blumenfeld, Harry Callahan and, in this case, Irving Penn. I close my eyes and I go through the rolodex in my head thinking of them all until I find the one that instinctively feels like the inspirational match for the task at hand. That’s not to say I set about slavishly ripping them off. I use them as my starting point, my jumping off point. They are my photographic moral compass. They show me the light, guide the way and keep me company. Once I push off and get underway I’m then going forward under my own steam. By the time I get to the other side I will have, hopefully, added enough of my own ingredients to the dish for it to taste new and different.

It makes more sense to me now why i am perpetually confused by the idea that rhetorics of display are primarily present directed. They always transport me to the past.